A Tudor Character Sketch: Gregory Trelawney

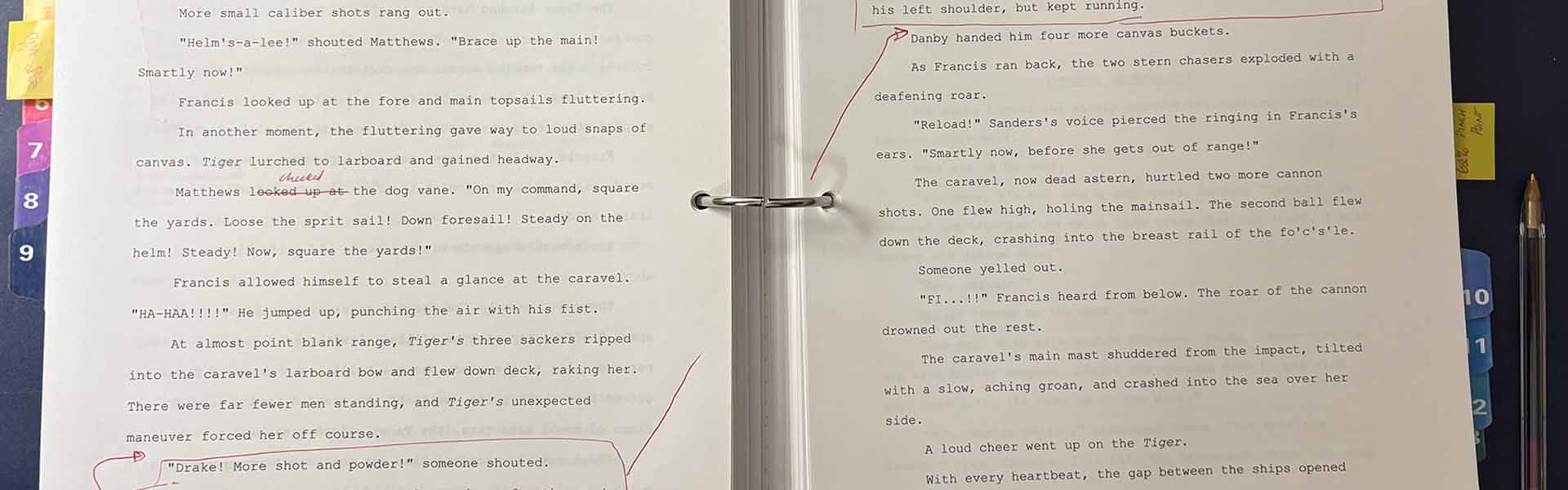

The twenty-three-year-old Gregory Trelawney is the main character in my yet-unnamed short story set against the backdrop of the 1544 Siege of Montreuil—the last great campaign of Henry VIII, and part of the Italian Wars. As an older and wiser Captain of the Tiger, he also appears in my historical fiction novel Sic Parvis Magna and short story Retribution.

My imagined Trelawney is no heir to great houses.

The real Trelawneys were one of the gentry families of Cornwall. It appears that they had several “seat” estates over the years, from Launceston to Menheniot and finally, in Pelynt. During Henry VIII’s rule, the Brightorre estate, which does not exist anymore, passed from Roger Trelawney to his daughter Joan Trelawney, who married Captain William Hawkins.

For the purposes of the story, I made up two siblings to Joan—an older brother who had, for a while, inherited the estate, and the younger Gregory Trelawney, who didn’t.

I also gave the Trelawneys a bit of a tarnished 16th-century reputation—social status during the Tudor period required many well-off families to spend a lot on the maintenance of their status, and it was not uncommon that many families went into debt. I gave the Trelawneys that imaginary burden.

Like so many younger sons of Tudor gentry, Gregory’s path was not inheritance but a vocation—at that time, it was church, law and civic service, or military service. (The landed gentry did not generally transition into freeman trades, though there is some evidence that suggests the real Trelawneys have).

Gregory Trelawney therefore had a mission to redeem his family name while he was starting his life.

War offered one of the few avenues for advancement, and in 1544 Henry VIII’s armies crossed the Channel with a strategy to seize key strategic targets—Boulogne and Montreuil.

The young Trelawney, caught between the genteel, idealized notions of honor and the harsh realities of Henry VIII’s last war—where villages were burned to the ground to deny succor to the enemy—now has to reconcile that polar opposition.

Serving under a commander embodied that very tension, the disillusionment could not have struck harder.

The seventy-one-year-old Duke of Norfolk, victor at Flodden a generation earlier, struggled before Montreuil, a fortress rebuilt with modern defenses. His army faced shortages of men and supplies. Outbreaks of sickness and his vicious justice claimed lives and morale. Finally, he and his planners underestimated the French resolve to ensure that Montreuil stood.

His cautious diplomacy, born of sober assessment, was turned against him by enemies at court. The old aristocrat realized how the Tudor war (and world) was changing faster than he could adapt and adopted victory-at-any-cost tactics, further adding to Trelawney’s internal conflict.

I’ll do another post on my research about the 1544 siege of Montreuil shortly.

When Howard was summoned to present himself before Henry VIII, Trelawney marched beneath the banner of Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey—Norfolk’s brilliant and headstrong son.

Surrey was a contradiction of the age. At Montreuil, the brilliant warrior-poet, whom Charles V commended for his military valor, was a reckless commander promoting his personal interests.

Aware of the likely effort to break the siege by the French, and probably envious of the fame of the military commander who successfully defended Montreuil (Marshal of France de Biez) he wanted to be seen acting decisively.

He acted impulsively. Surrey’s unauthorized assault on the Abbeville Gate nearly cost him his life.

In the real history of the seige, the Earl was saved only by the sacrifice of his squire, Thomas Clere, who succumbed less than a year later of the wounds he received while dragging the unconscious Surrey from the battle.

For this story, I modified history a little. Clere was seriously wounded while pulling Surrey to safety. Trelawney, bound by his idealistic perception of duty, charged in and saved both Surrey and Clere, also at great personal cost.

Surviving the battle became more than the need to heal or live through medical treatment that killed as many as died from cannon fire, ball shot, and arrows. For Trelawney—survival required a sacrifice. While recovering, he had to think through the real cost of his loyalty.

The hopeless offensive that claimed lives at random made him question what memento mori meant for him. He had to think about how he could live a worthy life and to “properly” prepare for death amidst the barbarism of total war.

The loss of others made him question his own purpose. (I’ll explore that in a later post).

Amidst the English military disaster at Montreuil, Trelawney found unexpected kinship. In the surgeon’s tent he encountered George Sampson, a brilliant military surgeon with an unsettling manner. I enjoyed writing his profile, and will post it in the near future as well.

Their conversations—wine-fueled, late-night debates about God, medicine, and the folly of men, as well as their survival in the crucible of a failing siege—bound them as brothers stronger than blood could.

The fate of the real Trelawney family is well documented: they adapted, they married well, they rose in the 17th century to prominence from their seat at Trelawne Manor.

Gregory’s story, imagined among them, is a story of a younger son in an age of upheaval. For him, the 1544 Siege is not just a battle. It burned away illusion and forced him to confront his ideas of mortality and loyalty.

Stay tuned for opening scenes of the short story about this!