Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey: The Last Knight of a Dead Age

An Old-World Aristocrat in the Tudor Age

Born around 1516, Henry Howard entered the world with expectations as towering as his bloodline was ancient—his family’s pedigree traced his lineage back to the Conquest.

Some of England’s finest humanist scholars polished the future earl’s intellect, adding layers of sophistication.

He was taught classical literature, rhetoric, and moral philosophy. He read Virgil's Aeneid not merely as poetry but as a handbook of noble conduct, seeing in Aeneas a mirror of his own destiny—born to serve his people through noble sacrifice. His later translation of portions of the Aeneid would reveal both his literary genius and his deep identification with the classical heroic ideal.

From his earliest years, Surrey learned that nobility was not merely a social rank but a sacred trust, carrying with it both unassailable privileges and weighty responsibilities, conferred by centuries of loyal service to the crown.

His father, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, had restored the family's fortunes through military genius at Flodden. His competency and political cunning at Henry VIII's court made him indispensable, keeping him in Henry VIII’s favor.

However, for all of Norfolk’s expertise and cunning, the Howards did not see the world changing. They were "old nobility" in a court increasingly dominated by what they disdainfully called "new men"—administrators, lawyers, and merchants who advanced through talent rather than birth.

Surrey came to the increasing conclusion that these encroachments on his birthright demanded constant assertion against those who would diminish its significance.

The Explosive Genius

Contemporary accounts consistently describe Surrey as possessing a mind of extraordinary quickness and power, equaled only by his unstable temperament. He was a personality of fascinating contradictions—as capable of insights and achievements that dazzled his critics, as of explosions of rage and reckless judgment that terrified those around him.

Along with Wyatt, Surrey revolutionized English poetry and paved the way for the sonnet form Shakespeare would later perfect. His wit could charm courtiers and leap from premise to conclusion with a speed that left others struggling.

This intellectual arrogance combined with aristocratic pride to create a toxic cocktail. Perhaps because ideas and insights came so easily to him, Surrey grew impatient with those who were ‘dull’ in comparison.

Surrey didn't merely disagree with people—he dismissed them as inferior; he genuinely believed that only breeding produced superior judgment. When Cromwell or Wolsey, or other "base-born" administrators contradicted him, Surrey experienced their opposition not as legitimate disagreement but as presumptuous insubordination.

The Warrior-Poet's Military Education

Surrey served under Charles V in Flanders around 1543, and at barely 26, Surrey found himself responsible for one of England's most important strategic positions, facing constant pressure from French forces seeking to recapture their lost city.

The Boulogne command revealed both Surrey's military talents and the seeds of his future problems. He showed genuine tactical skill, successfully repelling multiple French attempts to retake the city through a combination of innovative defensive strategies and personal courage. Contemporary accounts praise his ability to rally troops under fire and his willingness to share the dangers he asked them to face. Here was aristocratic leadership at its finest—the noble commander earning loyalty through competence and shared sacrifice.

Yet even in success, Surrey's character flaws undermine him.

His correspondence reveals growing frustration with what he saw as inadequate support and incompetent interference from court administrators. He chafed under the financial constraints that limited his ability to undertake offensive operations, viewing such limitations as insults to his military judgment rather than prudent resource management.

The French campaign also reinforced Surrey's romantic vision of warfare. Unlike the grinding sieges, Surrey's experiences at Boulogne allowed him to see himself as continuing the heroic tradition of English knights from Crécy to Agincourt—epic English victories in northern France. For Surrey, war was a theater for displaying noble virtue rather than an instrument of state policy. More importantly, it was an opportunity to prove the superiority of nobility over base-birth.

During the early Tudor period, the Duke of Norfolk's—his father’s—victory at Flodden destroying the Scottish army in 1513, established the Duke of Norfolk as one of a long line of great English generals.

For Surrey, these legends became the standards of English military glory he felt compelled to match or exceed.

Every command, every campaign became an opportunity to prove that the Howard military genius was hereditary. Surrey sought dramatic victories worthy of standing beside his father's legendary achievement.

The Siege of Montreuil: A Glorious Tudor Miscalculation

When Surrey arrived at Montreuil-sur-Mer in 1544 to serve under his father's command, he brought with him all the accumulated pressures, prejudices, and ambitions. The siege represented everything Surrey craved: military glory, a chance to prove his superiority to the "new men" who questioned aristocratic competence, and a stage upon which to display the Howards’ continued indispensability to the Tudor crown.

His quick intelligence allowed him to grasp the tactical situation rapidly. He understood that Martin du Biez, the Marshal of France, was a seasoned military leader who had successfully held the position against previous English assaults. And yet… he also knew that he was baseborn.

He recognized that time was running out as French relief forces assembled.

He grasped the technical challenges posed by Montreuil's updated fortifications and elevated position.

Yet rather than moderating his approach, this knowledge intensified Surrey's conviction that only bold action could break the deadlock, despite the meddling from Henry VIII’s court.

The intelligence reaching Surrey about a potentially weak gate—almost certainly French disinformation designed to lure the English into a trap—found fertile ground in a mind already predisposed to believe that aristocratic brilliance and daring would triumph over plebeian ‘professionalism.’

This was the opportunity that Surrey's chivalric worldview and lightning intellect had taught him to recognize: a chance for boldness.

Surrey’s Antagonist Role

In my historical fiction short story, Surrey is more than just an obstacle—he embodies an entire worldview that Trelawney must examine, understand, and reject. He represents the seductive power of romantic idealism in warfare, the dangerous beauty of aristocratic codes that prioritize personal honor over practical effectiveness, and the tragic consequences of confusing boldness with competence.

Surrey's antagonism toward characters like my protagonist, Trelawney, operates on multiple levels. On the surface, it manifests as the casual condescension of high nobility toward the lesser gentry—Surrey's assumption of his superior judgment in all matters, military and otherwise. Yet beneath this social arrogance lies a deeper philosophical conflict about duty, honor, and service in a changing world.

Where Trelawney might represent the emerging values of professional competence, moral conscience, and loyalty to principles, Surrey embodies the older traditions of feudal obligation, aristocratic privilege, and honor defined by social rank. Surrey's tragedy is not that these older values are entirely wrong, but that his rigid adherence to them blinds and prevents him from adapting to new circumstances.

Surrey's thematic purpose is to force other characters to confront the contradictions in their own beliefs about duty and honor. His presence raises questions such as if noble birth doesn't guarantee noble character, what does? If traditional codes of chivalry prove inadequate for modern warfare, what should replace them? If aristocratic privilege can't be justified by superior performance, how can any social hierarchy be defended?

The Tragic Arc: Nobility's Last Stand

Surrey’s flaws are inextricably linked to genuine virtues, and his ultimate failure to recognize alternatives represents the death of something beautiful. His misplaced aristocratic pride stems from a sincere belief in the moral obligations of leadership. His military recklessness reflects genuine courage and a willingness to share the dangers he asks others to face. His disdain for "new men" grows from his concern about the replacement of traditional social frameworks with mere administrative efficiency.

Conclusion: The Mirror of a Changing Age

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, stands at the crossroads between two worlds—the storied medieval England of his imagination and the early modern reality of the Tudor period. In the historical fiction short story A Fool’s Errand, his character is a warning about the dangers of refusing to adapt to changing circumstances, as well as questions of what is duty, the source of honor, and the nature of nobility.

Additional Reading

Tudor Historical Fiction Character Sketch of Gregory Trelawney

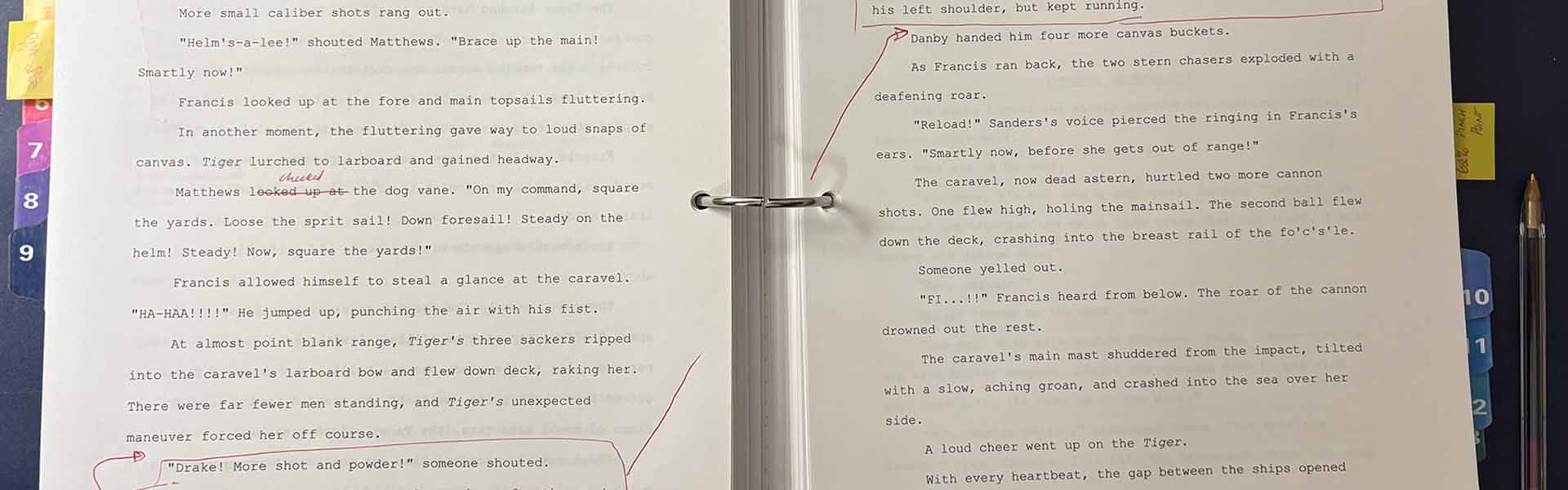

Francis Drake Character Sketch

Historical Fiction novel Sic Parvis Magna