Farm Boy to Pirate: A Character Sketch of Francis Drake

Brief Sketch of History of Drakes, Tavistock, and the Prayer Book Rebellion

How does a farm boy become one of the greatest naval heroes of one nation, a pirate scourge of another? How does a boy from an inland market town venture across the globe and become its second circumnavigator? Did the turmoil of his youth—fleeing his homestead, living with relatives, and multiple contemporaneous rebellions shape his world view, and if so, how?

The Drakes have lived in the Tavistock area for multiple generations, with the first records of the farm lease dating back to 1440s.1 The original lease from the Tavistock Abbey transitioned to the Russells following the Dissolution of the Monasteries Act. Francis Drake, born around 1540 (actual birthdate was lost to history), grew up on the family farm in Crowndale (just outside of Tavistock). The extended family lived together—grandparents John and Marjorie Drake, their son John Drake, their other son Edmund Drake, with his wife Mary Milwaye and Francis. Edmund and Mary had 12 boys, with Francis being the oldest.

Francis’ family was in good standing socially as well as economically. The Protestant Drakes benefitted from their relationship with the Protestant Earl of Bedford, whose son (then 13-year-old Francis Russell) stood as godfather to Francis Drake. The family also had close relations with the Hawkins and Fitz families. Economically, Turner comments that as yeomen farmers, the Drakes earned an “above-average” income—not wealthy, but far from destitute.

Life changed following England’s split with Rome. The Monastery Act of 1538 reallocated assets of the religious houses to the crown and its supporters. When Edward VI took the throne, the regent and the privy council (both of which had Protestant leanings) took the opportunity to further their gains, in the name of the boy king.

The parliament repealed the Six Articles of Henry VIII, allowed changes such as the marriage of the clergy and other changes. The Uniformity Act introduced the English language Book of Common Prayer, replacing Latin missals, and other changes removed Catholic vestiges of service.

While the Drakes were comparatively well off, there must have been many conversations about their neighbors’ financial well-being2 and the impact these changes may have on them. Francis would have overheard the concerns. The family was Protestant, so the new prayer book was likely not much of a concern. However, they were also a part of a community where most of the population was Catholic. From my perspective, it was likely that their lives became increasingly more difficult—such as the ability to take their farm’s products to market.

The April 1548 brought the appointment of a detested William Body3 to oversee removal of Catholic service items, another insult to the Catholic western counties like Cornwall and Devon. A crowd gathered outside of a Helston church where Body was. He ran and hid in a nearby house, but the crowd dragged him out and multiple people stabbed him to death.

The sessions courts were powerless to administer justice, and the local gentry could not control the populace. To regain some control over the situation, the crown issued a general pardon for the killing—with 28 exceptions who were executed for treason as examples. The crown ordered the display of4 the drawn and quartered remains of one person in Tavistock. A year later, right before the introduction of the new prayer book on Whitsunday, the Devonians and Cornishmen revolted. The rebels captured land, burned barns, marched and laid siege to Exeter before being put down by a mercenary force led by John Russell, the Earl of Bedford.

Edmund Drake fled from Tavistock after April 1548. (Edmund and two other men were accused of 2 assaults and robberies.)5 It is unclear that the assaults and robbery were separate from the events of the rebellion or somehow related, and if he took his family with him. Ultimately, Edmund’s family settles in Kent (where there was a more favorable religious climate and he and his wife had relations). During this turmoil, the 7-8-year-old Francis starts to live in Plymouth with William Hawkins, who was a brother to Francis’ grandmother Marjorie.

What impact did these events have on Francis’ world view? How would they shape his character to act in certain situations of stress?

Drawing Conclusions of Francis Drake’s Worldview

First, he experienced the class divisions early. While these hard divisions were an accepted societal norm, he had to have thought about and contrasted the opportunities available to his family versus what he saw in the house of William Hawkins, let alone those of the Russells. I wondered how this awareness sat with young Drake. My guess is that he, like all children, fantasized a lot about things he didn’t have—wealth and power, in his case.

However, I think a different want motivated him more than wealth.

There was a different “sub-elite” class of wealthy, land-owning merchants and knights. The elder William Hawkins was Drake’s principal example. Francis likely had seen that Hawkins had the freedom to profit from a variety of activities such as trade and privateering.

And, Hawkins did not just profit. He was lauded—elected to the mayorship of Plymouth, elected to Parliament, and later overseeing tax receipts for the port of Plymouth. All of this despite being briefly imprisoned after a conviction for piracy. I believe this contrast—the ability of Hawkins to increase his wealth and influence while his family was forced to flee—was vivid in Drake’s mind.

Living in the household of William Hawkins, young Drake must have learned that Hawkins’s early military service likely started this chain.

That experience gave him connections at court, capital, and most importantly, freedom to act. Drake’s 1560s slave trading voyages under John Hawkins reinforced that belief—where despite loud protests from the Spanish ambassador at court, Elizabeth publicly rebuked and privately invested in the voyages. The younger Hawkins received support and investment from respectable members of society to “trade.” (The investment syndicate included the queen and members of the Privy Council, and the “trade” involved the purchase, theft, or capture of people in Guinea to sell on the Spanish Main.)

In fact, Hawkins’s was a patriotic enterprise—a firm rebuke of papal authority to divide the world by the Treaty of Tordesillas and a rejection of Spanish right to restrict trade in the West Indies.

The lesson was that, like his father, John Hawkins profited from being an instrument of foreign policy for the queen. Drake used this blueprint to finance his circumnavigation and to profit from it.

While an eight-year-old boy does not come to such conscious conclusions, having such examples likely oriented him towards a different course. Returning to become a farmer was just not an option for a young man that craved freedom, wealth, and power to act.

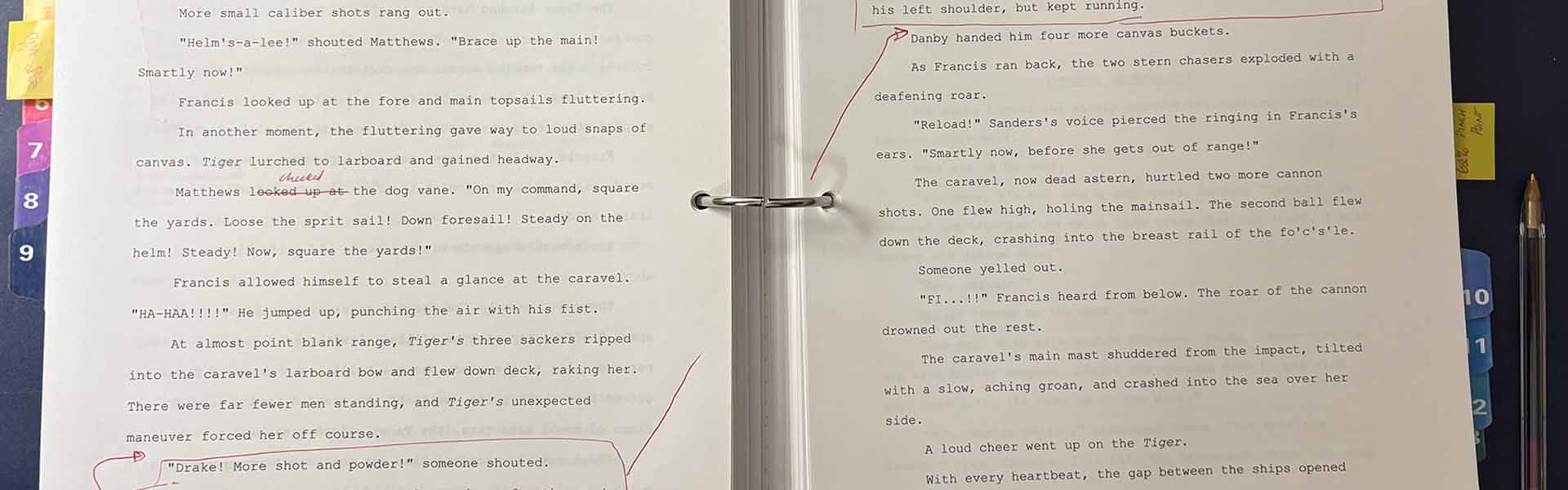

Applying This to the Plot in Sic Parvis Magna

In my historical fiction novel Sic Parvis Magna, I depict young Francis’ character as an inexperienced youth. He knows how to read, write, and count from his father’s schooling. His father’s religious beliefs also instilled a belief that whatever he did, Francis was fulfilling God’s plan for him.

The likely “why” question of his early life—the trauma of flight from Tavistock—had an answer.

William Hawkins provided the answers to the “why” and to the “how” for Drake.

Last Words on the Character Sketch of Francis Drake

Maritime trade was a very hazardous occupation. Francis Drake became an expert sailor, navigator, and merchant, honing Francis’ ability to survive adversity and reinforce his world view as an underdog. With this experience, he looked for opportunities to exploit because he believed that God was on his side. Sic Parvis Magna is on his coat of arms for that reason—from small things, greatness.

Want to see how this Drake steps into fiction? Read Chapter 1 of historical fiction novel Sic Parvis Magna.

Further Reading

Batcho, Krystine. “What Your Oldest Memories Reveal About You | Psychology Today.” Psychology Today, April 4, 2015. [https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/longing-nostalgia/201504/what-your-oldest-memories-reveal-about-you.

Heldring, Leander, James A Robinson, and Sebastian Vollmer. “The Long-Run Impact of the Dissolution of the English Monasteries,” n.d., 83.

Kelsey, H. Sir Francis Drake: The Queen’s Pirate. Nota Bene Series. Yale University Press, 2000.

Stone, Lawrence. The Crisis of the Aristocracy, 1558-1641. London: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Sturt, J. Revolt in the West: The Western Rebellion of 1549. Devon Books, 1987.

Sugden, John. Sir Francis Drake. 1st American. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 1990.

Turner, Michael. “In Drake’s Wake - The Real Francis Drake.” Accessed February 6, 2021. [http://www.indrakeswake.co.uk/Drake/realdrake.htm]{.underline}.

Turner, M., In Drake’s Wake (Mould:2005), p. 4 ↩︎

Refer to Heldring, et al. The Long-Run Impact of the Dissolution of the English Monasteries. In particular, it is interesting to observe that the re-allocation of the monastery land was theorized to have released the labor from the less efficient agricultural work to other pursuits and in several hundred years, resulted in higher levels of industrialization in England. My theory is that this also had an appreciable impact on the rents as the new landlords renegotiated leases—leading to the release of labor over time. ↩︎

Sturt, J., Revolt in the West (Devon Books:1987), p.14. Body was not an ordained priest, unqualified for the Archdeaconry and came into the position by, in effect, purchasing it. ↩︎

Ibid., p.15. ↩︎

Refer to Kelsey’s discussion of early history of Drakes. ↩︎