Sic Parvis Magna Sample Chapter—Family Dinner

Drake’s Crowndale farm had several houses, including a mill, cottages, and a traditional longhouse. The longhouse had one large hall with rush-covered floors and a hearth in the center, the smoke of which wafted up through the thatch.

A screen separated Francis’s grandparents’ sleeping area, and a few chests divided the space between the small windows.

After washing his hands, he sat at the center table with his grandparents, parents, and Uncle John. The smell of Grandmother’s stew and fresh bread filled the space, but only Francis seemed to notice.

As Francis scanned each person around the table, his relief vanished.

Edmund, his father, was solemn and quiet, his hands red and swollen. He flexed his fingers, pain evident on his face. After serving everyone, Mary, his mother, sat to apply salve to Edmund’s hands.

Grandfather stirred his stew, his expression dark.

Francis dried his hands on his slops. “Father, what happened to your hands?”

“Don’t mind that, Francis,” Mary said. “Eat your food.”

Francis waited for the familiar words of grace, but it did not come. No one joined him as he muttered the prayer—it was as if they did not even hear him. He sank his wooden spoon into the bowl of the piping-hot stew, pushing the pieces of meat and vegetables into his spoon with the bread.

“The common folk grumble about Somerset’s new prayer book,” Grandfather muttered. “Change never comes without a fight.”

Francis’s knot in his stomach returned. He shifted on the hard bench to get more comfortable.

“‘Tis not the first time they have seen church reform,” said Marjorie. Her breath was tight. “Nothing changed after King Henry dissolved the monasteries twelve years ago. We agreed to the same lease that we held from the abbey with Lord Russell.”

“Our patron, Lord Russell, belongs to the true church like us. He wants like-minded tenants on his lands,” said Edmund.

“Most folk weren’t as fortunate as we,” said John. “I know good men who’ve lost their leaseholds and were turned out.”

Grandfather nodded. “But a fortnight ago, Langiford was crying in his pottage about the new taxes on wool.”

“Mayhap he should sell mutton.” John’s mouth returned to a tight line.

Edmund shook his head.

“Langiford’s mill is busier than ever but still owes me twenty shillings.”

“By the rood, Edmund! How badly is Langiford hurt?” Grandfather demanded.

Francis’s spoonful of stew froze mid-air. He glanced at Grandfather, then at Edmund’s red hands.

“You shouldn’t have threatened him, Edmund. He will run to the Justice of the Peace and say you robbed him.”

Edmund nodded. “The Lord knows that was not the plan. Langiford and Harte owe me a round sum for wages. We need the money to leave Tavistock, and I don’t have time to listen to his tales of how hard life was for him.”

Francis’s stomach tightened. It was not the first time Edmund spoke of leaving Tavistock—but tonight, with all that had happened earlier, Francis felt even less at ease.

“I heard they quartered a Helston man for the Body murder,” said Grandfather.

“That’s what the bell ringing was for,” said John.

“When I went to the market earlier today, I was ill at ease. I went out of my way to avoid some people. People are angry,” said Mary.

“When common folk can’t feed their families, they look to someone to blame.” Grandfather rubbed his hands together in a way that Francis knew meant something troubled him.

“Tavistock won’t shelter us from this for much longer,” he added.

“They mean to tear down all the saints’ images in the churches,” said Francis in a small voice.

Everyone turned towards Francis. The crackle of the hearth fire was the only sound in the room.

“Whatever do you mean, son?” asked Mary.

Francis squirmed in his seat. He looked at his grandmother for assurance, took a deep breath, and described his conversation with the cook.

When he finished, he looked around him. Mary’s hands clasped the edge of the table, her knuckles white. Edmund’s jaw clenched, and Uncle John sat rigid.

“Start from the beginning, boy. Tell us what you saw and heard,” Grandfather said, his brows pinched together over his face.

Francis crossed his arms.

“Well, I hadn’t done nothing! I just delivered the eggs, like Grandmother asked!”

“Francis,” said Mary. “This is very important. What else did you see?”

“At the market, I wanted to see what the people were shouting about and squeezed through the crowd.”

He fidgeted in his seat.

“I saw a priest shouting at the crowd, but I did not hear what he said. The people shouted replies. I never saw that priest before—”

He trailed off as the adults exchanged worried looks.

John broke the silence.

“‘Tis getting worse. Lord Russell has not been in his lands for a long time, and there is no order in town. Nobody is supporting the King or his council on the true religion. Now, outsiders…”

Edmund raised his hand, stopping him. “And then what, Francis?”

“I went to the Fitzford house and delivered the eggs and cheese,” said Francis.

“Mistress Smith, the cook,” he added, his tone lifted. “She sends you her compliments, grandmother!”

Marjorie smiled, though the smile vanished quickly. “Did she say anything else, Francis?”

“She said to take care!”

Francis lowered his eyes and stared at his food.

“Francis, is there anything else?” asked Mary.

“I’m sorry, mother. I thought it would be all right to stop at James’s house for a little.”

“Is that all?” asked Mary.

“When I came up to James’s house…” Francis’s voice caught. “He refused to play with me.”

Grandfather exchanged a worried look with his sons.

“Why?” asked Edmund.

“He called me a heretic and said that he will have nothing more to do with me.”

Francis’s shoulders slumped as he picked at his food.

“Why did he do that?”

Mary stroked his head.

“Father… why do we need to leave? It is nice here.”

The adults exchanged uneasy glances.

“We would feel safer away from Tavistock,” said Marjorie. “There are many here that want to harm us.”

Edmund nodded.

“But why?” repeated Francis, turning towards his father.

Edmund thought for a second.

“Francis, do you remember when I said that you can speak to God directly and that all that you need to guide you is in the Bible? That God has a plan for you?”

Francis nodded.

“Well, those people in the marketplace believe that to talk to God, you must first talk to the priest in the church and to go to heaven, you must do certain things. They are afraid of our way. So, they throw rocks at us because we believe differently.”

Francis fought back his tears.

“Is that why James did not want to play with me? Can’t I tell him I can also talk to a priest, too?” He looked from one face to the next, looking for confirmation.

Mary’s gaze drifted off as she swiped a tear from her eye.

Grandfather looked at Edmund. “You’ll find no living reading prayers here.”

Edmund nodded.

Francis picked at his food for a little while longer and then quietly excused himself. He went back to the cottage where he and his parents lived, leaving the sweetbread untouched. Nobody heard him.

However, no sooner had he made ten paces down the path, he saw torchlight on top of the ridge, a mile or two out.

Read the next scene, from the historical fiction novel Sic Parvis Magna, “Escape from Tavistock”

Did you miss the start? Read the opening scene, Going on Delivery or the overview of the sample chapter.

Read my comments about who is real in Sic Parvis Magna.

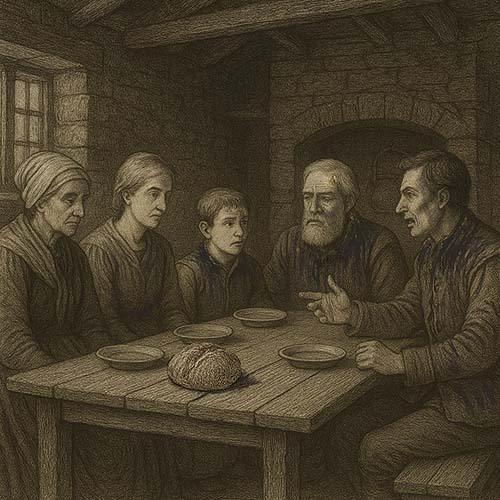

About The Illustration

The engraving was created with an AI generator, prompted on the contents of this scene and modified.